SEEDING JOY: THE ART OF HAIKU

honoring haiku, not as a rigid form, but as a listening practice—listening to seasons, to breath, to what is small and telling

What’s Your Winter Ritual?

Relaxing with a cup of tea/ Warming yourself…

Being in a space that brings you joy…

Stretching and breathing...

Know that you are welcome here.You are invited to open yourself to the experience.Please move at your own pace / return as it pleases you.

ESSENTIAL QUESTION: What Is Haiku?

A haiku is a traditional form of Japanese poetry known for its brevity, simplicity, and deep connection to nature and lived experience. Historically, classical Japanese haiku consist of three phrases (often represented in English as three lines) with seventeen syllables arranged in a 5–7–5 pattern — five syllables in the first line, seven in the second, and five in the third. Haiku are typically unrhymed and emphasize direct, sensory imagery to capture a moment in time or a vivid scene. They often include a seasonal reference (called kigo) that situates the poem in a particular time of year and evokes mood and context, and in traditional Japanese practice they also incorporate a cutting word (kireji) that creates a pause or juxtaposition between images.

Origins and Tradition

The form originated in 17th-century Japan, evolving from the opening stanza (hokku) of collaborative linked verse (renga). Over time, poets such as Matsuo Bashō elevated the hokku into a standalone art form, which later became known as haiku in the 19th century. Traditional haiku center on nature and seasonal observation, aiming to convey not just what is seen, but the felt essence of a moment. In Japanese, haiku were originally written in one continuous line and based on on (sound units), which don’t map perfectly to English syllables — so contemporary English haiku practices vary in syllable counts while preserving the form’s spirit and imagery.

Source: Encyclopedia Britannica

Notes From The Masters

Lineage & Expansion

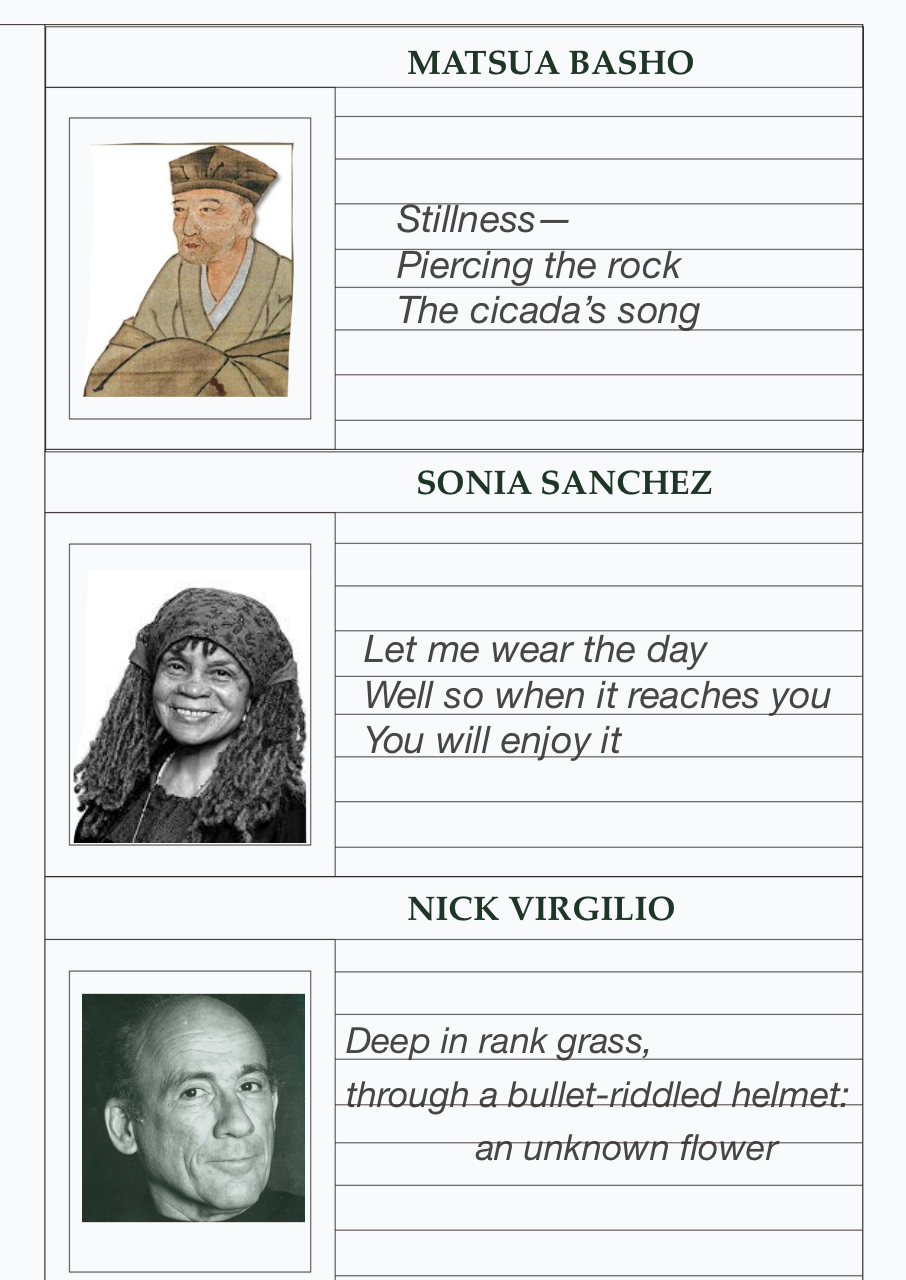

Matsuo Bashō (1644–1694)

Haiku as attention, not decoration

Rooted in seasonal awareness (kigo) and direct observation

Poetry as walking, noticing, being changed by the world

Bashō reminds us: the poem happens where you are standing.

Nick Virgilio (1928–1989) — Camden, NJ

Brought haiku into urban, working-class America

Focused on everyday life, public spaces, small mercies

Helped shape American haiku that centers place and presence, not syllable perfection

Virgilio showed us: a sparrow on asphalt belongs in the poem.

Sonia Sanchez (b. 1934)

Expanded haiku and monoku into Black poetic breath

Language as music, politics, intimacy, urgency

Her small poems compress feeling, protest, love into short, powerful lines

Sanchez teaches us: short poems can carry long histories.

Key Curatorial Note:

Haiku and monoku are living forms—they travel, adapt, and make room for many voices. This workshop invites respect for origin and freedom in practice.

Haiku Scaffold (5–7–5 Format)

Haiku is both a specific Japanese literary tradition and a living global form shaped by many communities.

Respect comes from naming the origin while welcoming expansion.

Traditional Seasonal Words (Kigo) Become More Flexible

In Japan, haiku traditionally includes a kigo, or season word, grounding the poem in nature’s cycle.

In English-language haiku:

poets may still use seasonal imagery

but the “season” may be urban, emotional, or cultural

Examples of expanded seasonal awareness:

police sirens signifying “summer”

warming centers as “winter”

wildfire smoke as “autumn”

Season becomes not only weather, but lived condition.

Cutting Words (Kireji) Become “The Turn”

Japanese haiku often include a kireji, or cutting word — a pause or pivot between two images.

English does not have cutting words in the same way, so poets often create the cut using:

punctuation (dash, ellipsis)

line breaks

juxtaposition

This creates the signature haiku effect:

Two images placed side-by-side that spark insight.

English haiku emphasizes this technique of juxtaposition and the “haiku moment.”

Line 1 (5 syllables)

Set the scene

Where are we?

What season or moment?

Example:

Cities screeching ICE!

Line 2 (7 syllables)

Add detail or action

What is happening?

What do you notice?

Example:

Steam rising from metal grates

Line 3 (5 syllables)

The turn or feeling

A surprise, shift, or quiet reflection

What does it reveal?

Example:

Hissing winters breath

Full Poem:

Cities screeching ICE! Steam rising from metal grates Hissing winters breath

Haiku Expands Beyond Nature Poetry

In the West, haiku was first introduced as “nature poetry,” but poets of many cultures have expanded the form to include:

city life

war

migration

racism

intimacy

grief

political struggle

joy

Nick Virgilio (Camden, NJ)

Virgilio helped establish American haiku as urban and working-class, paying attention to:

sparrows

alleyways

ordinary holiness

He showed that haiku belongs not only to mountains and temples, but also to sidewalks and bus stops.

The Haiku Society of America offers one of the clearest modern definitions:

“A haiku is a short poem that uses imagistic language to convey the essence of an experience… intuitively linked to the human condition.”

This definition emphasizes:

experience over syllables

image over explanation

intuition over ornament

Template:

Line 1 (5): Season / time / place

Line 2 (7): What you notice happening

Line 3 (5): A turn, feeling, or small truth

Prompts for Practice:

1. What is Winter? (Bashō Prompt)

Write a haiku about something small you noticed today that you might normally overlook.

Look for:

bare branches

sidewalk salt

steam rising

a quiet moment

2. City Seasons (Nick Virgilio Prompt)

Write a haiku set in Philadelphia winter — at a bus stop, corner store, rowhouse block, or schoolyard.

Focus on:

the ordinary city becoming sacred through attention.

3. The Turn (Juxtaposition Prompt)

Write a haiku that places two images side-by-side:

notice the cold while anticipating something warm

Example pairings:

shivering and moonlight, snow + laughter, silence + the scent from distant fireplaces

What is bringing warmth in a cold season?

4. Monoku Truth Line (Sonia Sanchez Prompt)

Write a monoku (one-line poem) that begins with:

“winter taught me…”

Let it hold feeling, memory, and/or resilience.

5. Lineage + Offering Prompt (Intergenerational)

Write a short poem to someone in another generation:

a grandparent

a child

your younger self

an ancestor

What would you want them to notice, remember or carry forward?

Use your preferred writing tools or use the digital notepad above, then copy and paste your work into the Google Form below .

Remember to have fun and break any rules that don’t speak to your soul.

—be inspired / learn more—